Psychoactive drug

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical or psychotropic is a chemical substance that crosses the blood-brain barrier and acts primarily upon the central nervous system where it alters brain function, resulting in changes in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition, and behavior.[1] These drugs may be used recreationally, to purposefully alter one's consciousness, as entheogens for ritual or spiritual purposes, as a tool for studying or augmenting the mind, or therapeutically as medication.

Because psychoactive substances bring about subjective changes in consciousness and mood that the user may find pleasant (e.g. euphoria) or advantageous (e.g. increased alertness), many psychoactive substances are abused, that is, used excessively, despite risks or negative consequences. With sustained use of some substances, physical dependence may develop, making the cycle of abuse even more difficult to interrupt. Drug rehabilitation aims to break this cycle of dependency, through a combination of psychotherapy, support groups and even other psychoactive substances.

In part because of this potential for abuse and dependency, the ethics of drug use are the subject of a continuing philosophical debate. Many governments worldwide have placed restrictions on drug production and sales in an attempt to decrease drug abuse. Ethical concerns have also been raised about over-use of these drugs clinically, and about their marketing by manufacturers.

Contents |

History

Drug use is a practice that dates to prehistoric times. There is archaeological evidence of the use of psychoactive substances dating back at least 10,000 years, and historical evidence of cultural use over the past 5,000 years.[2] While medicinal use seems to have played a very large role, it has been suggested that the urge to alter one's consciousness is as primary as the drive to satiate thirst, hunger or sexual desire.[3] The long history of drug use and even children's desire for spinning, swinging, or sliding indicates that the drive to alter one's state of mind is universal.[4]

This relationship is not limited to humans. A number of animals consume different psychoactive plants, animals, berries and even fermented fruit, becoming intoxicated, such as cats after consuming catnip. Traditional legends of sacred plants often contain references to animals that introduced humankind to their use.[5] Biology suggests an evolutionary connection between psychoactive plants and animals, as to why these chemicals and their receptors exist within the nervous system.[6]

During the 20th century, many governments across the world initially responded to the use of recreational drugs by banning them and making their use, supply or trade a criminal offense. A notable example of this is the Prohibition era in the United States, where alcohol was made illegal for 13 years. However, many governments have concluded that illicit drug use cannot be sufficiently stopped through criminalization. In some countries, there has been a move toward harm reduction by health services, where the use of illicit drugs is neither condoned nor promoted, but services and support are provided to ensure users have adequate factual information readily available, and that the negative effects of their use be minimized.

Uses

Psychoactive substances are used by humans for a number of different purposes. These uses vary widely between cultures. Some substances may have controlled or illegal uses while others may have shamanic purposes, and still others are used medicinally. Other examples would be social drinking or sleep aids. Caffeine is the world's most widely consumed psychoactive substance, but unlike many others, it is legal and unregulated in nearly all jurisdictions. In North America, 90% of adults consume caffeine daily.[7]

Psychoactive drugs are divided into 3 groups:[1]

- depressants - those that slow down the central nervous system; such as tranquillisers, alcohol, petrol, heroin and other opiates, cannabis (in low doses)

- stimulants- those that excite the nervous system; such as nicotine, amphetamines, cocaine, caffeine

- hallucinogens - those that alter how reality is perceived; such as LSD, mescaline, "magic mushrooms"

Anesthesia

General anesthetics are a class of psychoactive drug used on patients to block pain and other sensations. Most anesthetics induce unconsciousness, which allows patients to undergo medical procedures like surgery without physical pain or emotional trauma.[8] To induce unconsciousness, anesthetics affect the GABA and NMDA systems. For example, halothane is a GABA agonist,[9] and ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist.[10]

Pain control

Psychoactive drugs are often prescribed to manage pain. As the subjective experience of pain is regulated by endogenous opioid peptides, pain can be managed using psychoactives that operate on this neurotransmitter system as opioid receptor agonists. This class of drugs can be highly addictive, and includes opiate narcotics, like morphine and codeine.[11] NSAIDs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen, are a second class of analgesics. They reduce eicosanoid-mediated inflammation by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase.

Psychiatric medication

Psychiatric medications are prescribed for the management of mental and emotional disorders. There are 6 major classes of psychiatric medications:

- Antidepressants, which are used to treat disparate disorders such as clinical depression, dysthymia, anxiety, eating disorders and borderline personality disorder.[12]

- Stimulants, which are used to treat disorders such as attention deficit disorder and narcolepsy and to suppress the appetite.

- Antipsychotics, which are used to treat psychoses, schizophrenia and mania.

- Mood stabilizers, which are used to treat bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

- Anxiolytics, which are used to treat anxiety disorders.

- Depressants, which are used as hypnotics, sedatives, and anesthetics.

Recreational use

Many psychoactive substances are used for their mood and perception altering effects, including those with accepted uses in medicine and psychiatry. Examples include caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, LSD, and cannabis.[13] Classes of drugs frequently used recreationally include:

- Stimulants, which activate the central nervous system. These are used recreationally for their euphoric effects.

- Hallucinogens (psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants), which induce perceptual and cognitive distortions.

- Hypnotics, which depress the central nervous system. These are used recreationally because of their euphoric effects.

- Opioid Analgesics, which also depress the central nervous system. These are used recreationally because of their euphoric effects.

- Inhalants, in the forms of gas aerosols, or solvents, which are inhaled as a vapor because of their stupefying effects. Many inhalants also fall into the above categories (such as nitrous oxide which is also an analgesic).

In some modern and ancient cultures, drug usage is seen as a status symbol. Recreational drugs are seen as status symbols in settings such as at nightclubs and parties.[14] For example, in ancient Egypt, gods were commonly pictured holding hallucinogenic plants.[15]

Because there is controversy about regulation of recreational drugs, there is an ongoing debate about drug prohibition. Critics of prohibition believe that regulation of recreational drug use is a violation of personal autonomy and freedom.[16] In the United States, critics have noted that prohibition or regulation of recreational and spiritual drug use might be unconstitutional.[17]

Ritual and spiritual use

Certain psychoactives, particularly hallucinogens, have been used for religious purposes since prehistoric times. Native Americans have used mescaline-containing peyote cacti for religious ceremonies for as long as 5700 years.[18] The muscimol-containing Amanita muscaria mushroom was used for ritual purposes throughout prehistoric Europe.[19] Various other hallucinogens, including jimsonweed, psilocybin mushrooms, and cannabis have been used in religious ceremonies for millennia.[20]

The use of entheogens for religious purposes resurfaced in the West during the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 70s. Under the leadership of Timothy Leary, new religious movements began to use LSD and other hallucinogens as sacraments.[21] In the United States, the use of peyote for ritual purposes is protected only for members of the Native American Church, which is allowed to cultivate and distribute peyote. However, the genuine religious use of Peyote, regardless of one's personal ancestry, is protected in Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Oregon.[22]

Military

Psychoactive drugs have been used in military applications as non-lethal weapons. In World War II, between 1939 and 1945, 60 million amphetamine pills were made for use by soldiers.

Administration

For a substance to be psychoactive, it must cross the blood-brain barrier so it can affect neurochemical function. Psychoactive drugs are administered in several different ways. In medicine, most psychiatric drugs, such as fluoxetine, quetiapine, and lorazepam are ingested orally in tablet or capsule form. However, certain medical psychoactives are administered via inhalation, injection, or rectal suppository/enema. Recreational drugs can be administered in several additional ways that are not common in medicine. Certain drugs, such as alcohol and caffeine, are ingested in beverage form; nicotine and cannabis are often smoked; peyote and psilocybin mushrooms are ingested in botanical form or dried; and certain crystalline drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamines are often insufflated (inhaled or "snorted"). The efficiency of each method of administration varies from drug to drug.[23]

Effects

Psychoactive drugs operate by temporarily affecting a person's neurochemistry, which in turn causes changes in a person's mood, cognition, perception and behavior. There are many ways in which psychoactive drugs can affect the brain. Each drug has a specific action on one or more neurotransmitter or neuroreceptor in the brain.

Drugs that increase activity in particular neurotransmitter systems are called agonists. They act by increasing the synthesis of one or more neurotransmitters or reducing its reuptake from the synapses. Drugs that reduce neurotransmitter activity are called antagonists, and operate by interfering with synthesis or blocking postsynaptic receptors so that neurotransmitters cannot bind to them.[24]

Exposure to a psychoactive substance can cause changes in the structure and functioning of neurons, as the nervous system tries to re-establish the homeostasis disrupted by the presence of the drug. Exposure to antagonists for a particular neurotransmitter increases the number of receptors for that neurotransmitter, and the receptors themselves become more sensitive. This is called sensitization. Conversely, overstimulation of receptors for a particular neurotransmitter causes a decrease in both number and sensitivity of these receptors, a process called desensitization or tolerance. Sensitization and desensitization are more likely to occur with long-term exposure, although they may occur after only a single exposure. These processes are thought to underlie addiction.[25]

Affected neurotransmitter systems

The following is a brief table of notable drugs and their primary neurotransmitter, receptor or method of action. It should be noted that many drugs act on more than one transmitter or receptor in the brain.[26]

| Neurotransmitter/receptor | Classification | Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

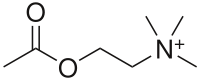

Cholinergics (acetylcholine agonists) | nicotine, piracetam |

| Anticholinergics (acetylcholine antagonists) | scopolamine, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, atropine, most tricyclics | |

|

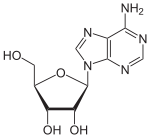

Adenosine receptor antagonists[27] | caffeine, theobromine, theophylline |

|

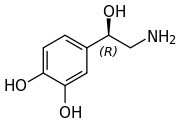

Dopamine reuptake inhibitors (DRIs) | cocaine, methylphenidate, amphetamine, bupropion |

| Dopamine releasers | amphetamine, agomelatine | |

| Dopamine agonists | pramipexole, L-DOPA (prodrug) | |

| Dopamine receptor antagonists | haloperidol, droperidol, many antipsychotics | |

|

GABA reuptake inhibitors | tiagabine |

| GABA receptor agonists | ethanol, barbiturates, diazepam and other benzodiazepines, zolpidem and other nonbenzodiazepines, muscimol, ibotenic acid | |

| GABA antagonists | thujone, bicuculline | |

|

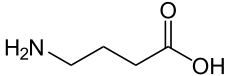

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | most non-SSRI antidepressants such as amoxapine, atomoxetine, bupropion, venlafaxine and the tricyclics |

| Norepinephrine releasers | mianserin, mirtazapine | |

|

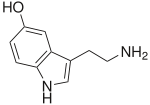

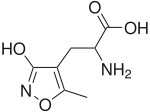

Serotonin receptor agonists | LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, DMT |

| Serotonin reuptake inhibitors | most antidepressants including tricyclics such as imipramine, SSRIs such as fluoxetine and sertraline and SNRIs such as venlafaxine | |

| Serotonin releasers | MDMA (ecstasy), mirtazapine | |

| Serotonin receptor antagonists | ritanserin, mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone, cyproheptadine, atypical antipsychotics | |

|

AMPA receptor antagonists | kynurenic acid, NBQX |

|

Cannabinoid receptor agonists | THC, cannabidiol, cannabinol |

| Cannabinoid receptor inverse agonists | Rimonabant | |

|

|

Melanocortin receptor agonists | bremelanotide |

|

|

NMDA receptor antagonists | ethanol, ketamine, PCP, DXM, Nitrous Oxide |

|

|

GHB receptor agonists | GHB, T-HCA |

|

|

μ-opioid receptor agonists | morphine, heroin, oxycodone, codeine |

| μ-opioid receptor inverse agonists | naloxone, naltrexone | |

| κ-opioid receptor agonists | salvinorin A, butorphanol, nalbuphine | |

| κ-opioid receptor inverse agonists | buprenorphine | |

|

|

H1 histamine receptor antagonists | diphenhydramine, doxylamine, mirtazapine, mianserin, quetiapine, most tricyclics |

|

|

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) | phenelzine, iproniazid, tranylcypromine |

| bind to MAO protein transporter | amphetamine, methamphetamine |

Addiction

.svg.png)

Psychoactive drugs are often associated with addiction. Addiction can be divided into two types: psychological addiction, by which a user feels compelled to use a drug despite negative physical or societal consequence, and physical dependence, by which a user must use a drug to avoid physically uncomfortable or even medically harmful withdrawal symptoms.[29] Not all drugs are physically addictive, but any activity that stimulates the brain's dopaminergic reward system — typically, any pleasurable activity[30] — can lead to psychological addiction.[29] Drugs that are most likely to cause addiction are drugs that directly stimulate the dopaminergic system, like cocaine and amphetamines. Drugs that only indirectly stimulate the dopaminergic system, such as psychedelics, are not as likely to be addictive.

Many professionals, self-help groups, and businesses specialize in drug rehabilitation, with varying degrees of success, and many parents attempt to influence the actions and choices of their children regarding psychoactives.[31]

Common forms of rehabilitation include psychotherapy, support groups and pharmacotherapy, which uses psychoactive substances to reduce cravings and physiological withdrawal symptoms while a user is going through detox. Methadone, itself an opioid and a psychoactive substance, is a common treatment for heroin addiction. Recent research on addiction has shown some promise in using psychedelics such as ibogaine to treat and even cure addictions, although this has yet to become a widely accepted practice.[32][33]

Legality

The legality of psychoactive drugs has been controversial through most of recent history; the Opium Wars and Prohibition are two historical examples of legal controversy surrounding psychoactive drugs. However, in recent years, the most influential document regarding the legality of psychoactive drugs is the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, an international treaty signed in 1961 as an Act of the United Nations. Signed by 73 nations including the United States, the USSR, India, and the United Kingdom, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs established Schedules for the legality of each drug and laid out an international agreement to fight addiction to recreational drugs by combatting the sale, trafficking, and use of scheduled drugs.[34] All countries that signed the treaty passed laws to implement these rules within their borders. However, some countries that signed the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, such as the Netherlands, are more lenient with their enforcement of these laws.[35]

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authority over all drugs, including psychoactive drugs. The FDA regulates which psychoactive drugs are over the counter and which are only available with a prescription.[36] However, certain psychoactive drugs, like alcohol, tobacco, and drugs listed in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs are subject to criminal laws. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 regulates the recreational drugs outlined in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.[37] Alcohol is regulated by state governments, but the federal National Minimum Drinking Age Act penalizes states for not following a national drinking age.[38] Tobacco is also regulated by all fifty state governments.[39] Most people accept such restrictions and prohibitions of certain drugs, especially the "hard" drugs, which are illegal in most countries.[40][41][42]

At the beginning of the 21st century, legally prescribed illegal psychoactive drugs used for legitimate purposes have been targeted by the US Justice System.[43]

In the medical context, psychoactive drugs as a treatment for illness is widespread and generally accepted. Little controversy exists concerning over the counter psychoactive medications in antiemetics and antitussives. Psychoactive drugs are commonly prescribed to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, certain critics believe that certain prescription psychoactives, such as antidepressants and stimulants, are overprescribed and threaten patients' judgement and autonomy.[44][45]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "CHAPTER 1 Alcohol and Other Drugs". ISBN 0724533613. http://www.nt.gov.au/health/healthdev/health_promotion/bushbook/volume2/chap1/sect1.htm.

- ↑ Merlin, M.D (2003). "Archaeological Evidence for the Tradition of Psychoactive Plant Use in the Old World". Economic Botany 57 (3): 295–323. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0295:AEFTTO]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Siegel, Ronald K (2005). Intoxication: The Universal Drive for Mind-Altering Substances. Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont. ISBN 1-59477-069-7.

- ↑ Weil, Andrew (2004). The Natural Mind: A Revolutionary Approach to the Drug Problem (Revised edition). Houghton Mifflin. pp. 15. ISBN 0-618-46513-8.

- ↑ Samorini, Giorgio (2002). Animals And Psychedelics: The Natural World & The Instinct To Alter Consciousness. Park Street Press. ISBN 0-89281-986-3.

- ↑ Albert, David Bruce, Jr. (1993). "Event Horizons of the Psyche". http://www.csp.org/chrestomathy/event_horizons.html. Retrieved February 2, 2006.

- ↑ Lovett, Richard; Flögel, U; Jacoby, C; Hartwig, HG; Thewissen, M; Merx, MW; Molojavyi, A; Heller-Stilb, B et al. (24 September 2005). "Coffee: The demon drink?" (fee required). New Scientist 18 (2518): 577–9. doi:10.1096/fj.03-0496fje.; (inactive 2008-06-25). PMID 14734644. http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=mg18725181.700. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Medline Plus. Anesthesia. Accessed on July 16, 2007.

- ↑ Li X, Pearce RA (2000). "Effects of halothane on GABA(A) receptor kinetics: evidence for slowed agonist unbinding". J. Neurosci. 20 (3): 899–907. PMID 10648694.

- ↑ Harrison N, Simmonds M (1985). "Quantitative studies on some antagonists of N-methyl D-aspartate in slices of rat cerebral cortex". Br J Pharmacol 84 (2): 381–91. PMID 2858237.

- ↑ Quiding H, Lundqvist G, Boréus LO, Bondesson U, Ohrvik J (1993). "Analgesic effect and plasma concentrations of codeine and morphine after two dose levels of codeine following oral surgery". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 44 (4): 319–23. doi:10.1007/BF00316466. PMID 8513842.

- ↑ Schatzberg, A.F. (2000). "New indications for antidepressants". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61 (11): 9–17. PMID 10926050.

- ↑ Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence by the World Health Organization. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ↑ Anderson TL (1998). "Drug identity change processes, race, and gender. III. Macrolevel opportunity concepts". Substance use & misuse 33 (14): 2721–35. doi:10.3109/10826089809059347. PMID 9869440.

- ↑ Bertol E, Fineschi V, Karch S, Mari F, Riezzo I (2004). "Nymphaea cults in ancient Egypt and the New World: a lesson in empirical pharmacology". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97 (2): 84–5. doi:10.1258/jrsm.97.2.84. PMID 14749409.

- ↑ Hayry M (2004). "Prescribing cannabis: freedom, autonomy, and values". Journal of medical ethics 30 (4): 333–6. doi:10.1136/jme.2002.001347. PMID 15289511.

- ↑ Barnett, Randy E. "The Presumption of Liberty and the Public Interest: Medical Marijuana and Fundamental Rights". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ↑ El-Seedi HR, De Smet PA, Beck O, Possnert G, Bruhn JG (2005). "Prehistoric peyote use: alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas". Journal of ethnopharmacology 101 (1-3): 238–42. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.022. PMID 15990261.

- ↑ Vetulani J (2001). "Drug addiction. Part I. Psychoactive substances in the past and presence". Polish journal of pharmacology 53 (3): 201–14. PMID 11785921.

- ↑ Hall, Andy. Entheogens and the Origins of Religion. Retrieved on May 13, 2007.

- ↑ Becker HS (1967). "History, culture and subjective experience: an exploration of the social bases of drug-induced experiences". Journal of health and social behavior (American Sociological Association) 8 (3): 163–76. doi:10.2307/2948371. PMID 6073200. http://jstor.org/stable/2948371.

- ↑ Bullis RK (1990). "Swallowing the scroll: legal implications of the recent Supreme Court peyote cases". Journal of psychoactive drugs 22 (3): 325–32. PMID 2286866.

- ↑ United States Food and Drug Administration. CDER Data Standards Manual. Retrieved on May 15, 2007.

- ↑ Seligman, Martin E.P. (1984). "4". Abnormal Psychology. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 039394459X.

- ↑ "University of Texas, Addiction Science Research and Education Center". http://www.utexas.edu/research/asrec/dopamine.html. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Lüscher C, Ungless M (2006). "The mechanistic classification of addictive drugs". PLoS Med. 3 (11): e437. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030437. PMID 17105338.

- ↑ Ford, Marsha. Clinical Toxicology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001. Chapter 36 - Caffeine and Related Nonprescription Sympathomimetics. ISBN 0721654851

- ↑ PMID 17382831 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ 29.0 29.1 Johnson, Brian. (2002) Psychological Addiction, Physical Addiction, Addictive Character, and Addictive Personality Disorder: A Nosology of Addictive Disorders. Retrieved on July 5, 2007.

- ↑ Zhang J, Xu M (2001). "Toward a molecular understanding of psychostimulant actions using genetically engineered dopamine receptor knockout mice as model systems". J Addict Dis 20 (3): 7–18. doi:10.1300/J069v20n04_02. PMID 11681595.

- ↑ Hops H, Tildesley E, Lichtenstein E, Ary D, Sherman L (1990). "Parent-adolescent problem-solving interactions and drug use". The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse 16 (3-4): 239–58. doi:10.3109/00952999009001586. PMID 2288323.

- ↑ "Psychedelics Could Treat Addiction Says Vancouver Official". http://thetyee.ca/News/2006/08/09/Psychedelics/. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Ibogaine research to treat alcohol and drug addiction". http://www.maps.org/ibogaine/. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ↑ MacCoun R, Reuter P (1997). "Interpreting Dutch cannabis policy: reasoning by analogy in the legalization debate". Science 278 (5335): 47–52. doi:10.1126/science.278.5335.47. PMID 9311925.

- ↑ History of the Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved at FDA's website on June 23, 2007.

- ↑ United States Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Retrieved from the DEA's website on June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Title 23 of the United States Code, Highways. Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Taxadmin.org. State Excise Tax Rates on Cigarettes. Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ↑ "What's your poison?". Caffeine. http://www.abc.net.au/quantum/poison/caffeine/caffeine.htm. Retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ↑ Griffiths, RR (1995). Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress (4th edition). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 2002. ISBN 0-7817-0166-X.

- ↑ Edwards, Griffith (2005). Matters of Substance: Drugs--and Why Everyone's a User. Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 352. ISBN 0-312-33883-X.

- ↑ Mosher, Clayton James; Scott Akins (2007). Drugs and Drug Policy: The Control of Consciousness Alteration. Sage. ISBN 0761930078.

- ↑ Dworkin, Ronald. Artificial Happiness. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006. pp.2-6. ISBN 0786719338

- ↑ Manninen BA (2006). "Medicating the mind: a Kantian analysis of overprescribing psychoactive drugs". Journal of medical ethics 32 (2): 100–5. doi:10.1136/jme.2005.013540. PMID 16446415.

External links

- Journal of Psychoactive Drugs: The first journal established to discuss drugs and drug abuse in the United States. (Wikipedia article about the website: Journal of Psychoactive Drugs)

- Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence by the WHO

- Research into the cerebral and neuronal effects of drugs use

- Erowid: Extensive online library primarily relating to psychoactive drugs

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||